- Lectures / Webinars

- 1. Management of spasticity in children with cerebral palsy Part I

1. Management of spasticity in children with cerebral palsy Part I

HotManagement of Spasticity in Children with Cerebral Palsy

This continuing medical education presentation will address an integrated approach to the management of spasticity in the pediatric patient with cerebral palsy.

The educational objectives of this CME initiative are to:

- Outline the pathophysiological basis of cerebral palsy and the resultant abnormalities of neuromuscular function.

- Describe techniques to assess the anatomic and functional impairments of patients with cerebral palsy

- Discuss the pharmacological, surgical and rehabilitative approaches to improving the function and quality of life in patients with cerebral palsy.

- Identify the benefits, side effects and complications of treatment of muscle overactivity and spasticity in patients with cerebral palsy.

Section Index

- Management of spasticity in children with cerebral palsy Part I

- Management of spasticity in cerebral palsy Part II Passive and Active Examination

- Management of spasticity in cerebral palsy Part III Treatment of Patients with cerebral palsy and spasticity

- Management of spasticity in cerebral palsy Part IV - Rehabilitation Management

- Oral Medications for the Treatment of Spasticity

- Intrathecal Baclofen for Spasticity in Cerebral Palsyy

- Local Anesthetics, Neurolytics, and Chemodenervation for the Patient with Cerebral Palsy and Spasticity

- Management of spasticity in cerebral palsy Part VIII -Botulinum Toxin

- Neurosurgical Interventions for Spasticity in Children with Cerebral Palsy

- Orthopedic Interventions for Spasticity in Children with Cerebral Palsyy

- Management of spasticity in cerebral palsy Part XI-Alternative Medicine in Spasticity Management

- Management of spasticity in cerebral palsy Part XII Case Studies

- Management of spasticity in cerebral palsy Part XIII Document Downloads

- Self Assessment

Disclaimer: The material presented in this course represents the clinical experience of the faculty, as well as current information obtained from the literature and includes discussions of off-label indications for various agents used to treat spasticity and muscle overactivity in children with cerebral palsy.

Cerebral Palsy

Definition Cerebral palsy is a group of disorders of motion and posture caused by a brain insult or injury occurring before the age of 2-years, the period of early cerebral development. While the definitive lesion responsible for the disorder is static, the clinical course of these patients is often progressive.

Incidence of CP

Improvements in prenatal and perinatal care have minimized CNS injury that leads to CP. However, neonatal ICUs have increased survival of children with brain injuries resulting in a relatively constant incidence of the disorder of approximately 2- 3:1000 live births. While the risk of the disorder is high in low birthweight neonates, the prevalence remains high in infants born at term. Specific abnormal findings on electronic monitoring of the fetal heart rate are also associated with an increased risk of cerebral palsy. Patients with cerebral palsy have a 30-year survival rate of approximately 87%. Approximately 500,000 children and adults of all ages have cerebral palsy.

March of Dimes Defects Foundation. Cerebral palsy. (Accessed January 2001).

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Cerebral palsy: hope through research. (Accessed January 2001).

Nelson KB, Dambrosia JM, Ting TY, et al. Uncertain value of electronic fetal monitoring in predicting cerebral palsy. N Engl J Med 1996;334:613-8.

Etiology

The insult resulting in cerebral palsy can be prenatal, natal, or postnatal. Specific etiologies that are associated with cerebral palsy include:

- 50%: Birthweight

- 10-20%: Intrapartum asphyxia

- 10-18%: Postnatal

- 12-30%: Other causes (brain malformation, arteriovenous malformation, unknown, etc)

Prenatal disorders that can result in cerebral palsy include congenital brain lesions (eg, arteriovenous malformations), intrauterine infections with a variety of organisms (eg, cytomegalovirus, rubella, Toxoplasma gondii), hemolytic disease of the newborn (Rh/ABO), or fetal anoxia from whatever causes. Abnormalities of coagulation (eg, antiphospholipid antibodies) may also be responsible for some cases.

Alternately, maternal disorders such as substance abuse, metabolic disturbances, and mental retardation are also associated with the development of cerebral palsy in some newborns. Problems at the time of delivery such as prematurity, trauma, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, and infection are also linked to the development of cerebral palsy.

During the postnatal period, a variety of disorders can result in the development of cerebral palsy. These include hypoxia and acidosis, infection (eg, meningitis, encephalitis, sepsis), traumatic head injuries and toxins such as lead. In some instances, the exact timing and etiology are unknown.

Ref: Nelson KB, Dambrosia JM, Grether JK, et al. Neonatal cytokines and coagulation factors in children with cerebral palsy. Ann Neurol 1998;44:665-75.

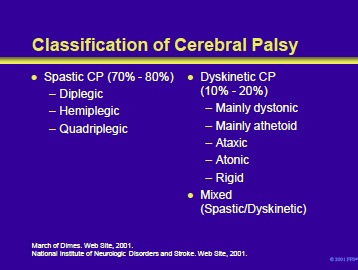

Patients with cerebral palsy can be classified by their type of abnormal tone into spastic (diplegic, hemiplegic and quadriplegic) cerebral palsy and dyskinetic (mainly dystonic or athetoid, ataxic or atonic) cerebral palsy.

The spastic type is discussed in the following slides. In patients with dyskinetic cerebral palsy, the primary site of pathology is in the striatum and the thalamus, areas with the highest concentration of glutamate receptors. Inability to synthesize or transport GABA may contribute to the clinical manifestations.

- Dystonic cerebral palsy manifests as sustained muscle contractions with resultant abnormal postures, twisting or repetitive movements. It usually begins at 3-5 years of age, changes as the brain matures and does not result in contractures.

- Athetoid cerebral palsy manifests as slow writhing movements of the distal musculature. Sixty-five percent of patients with this disorder present by the age of 2 years. Although they have a motor disorder and their postural reflexes are spared, children with athetoid cerebral palsy are intellectually spared.

Notably, spastic and dyskinetic movement disorders are frequently seen in the same patient (mixed presentation). In some instances, severe spasticity may mask the movement disorder. Therefore, the patients are defined by their predominant symptoms.

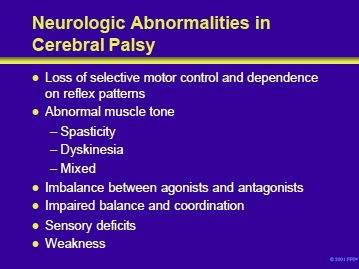

Major neurologic deficits in patients with cerebral palsy include the following:

- Loss of selective motor control and dependence on reflex patterns

- Abnormal muscle tone that is influenced by position, posture or movement:

- Spasticity

- Dyskinesia

- Mixed

- Relative imbalance between muscle agonists and antagonists

- Impaired body balance and coordination mechanisms

- Sensory deficits

- Weakness

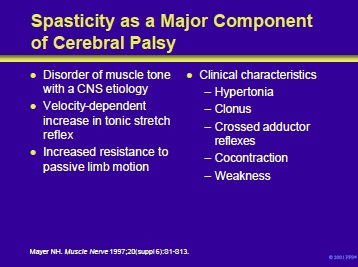

Spasticity, a disorder of muscle tone with its origin within the central nervous system, is usually a major component of cerebral palsy. It manifests as a velocity-dependent increase in tonic stretch reflex.

Patients with spasticity show increased resistance to passive limb motion.

Clinical characteristics of spasticity include the following:

- Hypertonia

- Clonus

- Crossed adductor reflexes

- Cocontraction of agonist and antagonist muscles is a major problem.

Symptoms of the upper motoneuron syndrome can be divided into positive and negative categories:

- Positive symptoms include spasticity and released flexor reflexes

- Negative symptoms include loss of finger dexterity, weakness and loss of selective control of muscles and limb segments.

Ref: Mayer NH. Clinicophysiologic concepts of spasticity and motor dysfunction in adults with an upper motoneuron lesion. Muscle Nerve 1997;20(suppl 6):S1-S13.

Neurophysiology of spasticity

The central nervous system includes the pyramidal and extrapyramidal systems. There are complex interconnections between these systems and the spinal cord. 1

Spasticity is due to a chronic reduction in inhibition. Loss of presynaptic inhibition results from the inability to synthesize or transport g-aminobutyric acid (GABA) to the anterior horn cell. Alterations in the membrane properties, synaptic input and a change in continuous descending inhibition produce the characteristic hyperexcitability of motor neurons.2

- Dormans JP, Pellegrino L. Definitions, Etiology, and Epidemiology of Cerebral Palsy. In: Caring for Children with Cerebral Palsy. 2nd ed. Baltimore, Md: Paul H Brooks Publishing Co; 2000:3-30.

- Mayer NH. Spasticity and the stretch reflex. Muscle Nerve 1997;20(suppl 6):S1-S13.

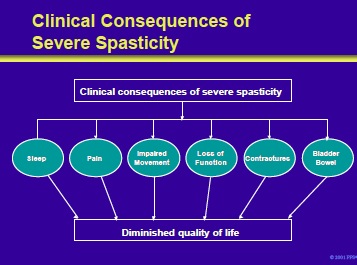

The clinical consequences of severe spasticity diminish the quality of life. They include:

- Impaired sleep

- Pain

- Impaired movement

- Loss of function

- Contractures

- Disturbances of bladder and bowel function

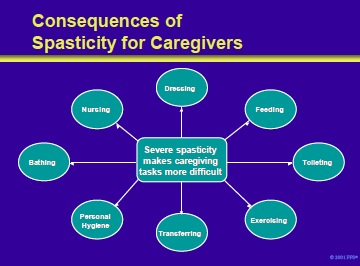

Severe spasticity also has significant consequences for caretakers. It makes it more difficult to care for the patient in a number of areas including:

- Dressing the patient

- Feeding • Toileting

- Exercising

- Transferring

- Personal hygiene

- Bathing

- Nursing

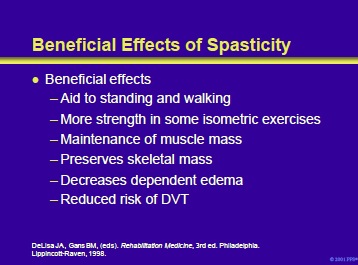

Beneficial effects include the following:

- Extensor tone may help the patient to stand.

- Hyperactive stretch reflexes may provide strength in isometric and eccentric voluntary contractions.

- Spasticity may help maintain muscle mass and prevent bone demineralization resulting from a lack of weightbearing and disuse.

- By acting as a muscle pump, spasticity may decrease dependent edema and reduce the risk of DVT.

Little JW, Massagli TL. Spasticity and associated abnormalities of muscle tone. In: DeLisa JA, Gans BM, (eds). Rehabilitation Medicine, 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA. Lippincott-Raven, 1998

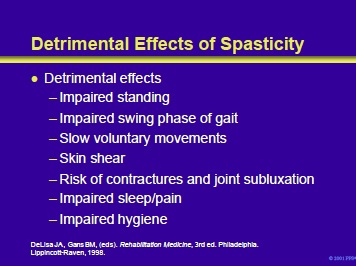

Detrimental effects of spasticity include the following:

- Impaired standing resulting from the effects of clonus, hip adductor scissoring and flexor spasms.

- Extensor spasms and clonus may impair gait. • Velocity-dependent hypertonus may slow voluntary movements.

- Flexor and extensor spasms may produce skin shear and impair positioning.

- Tonic hyperreflexia or flexor spasms can increase the risk of contractures and joint subluxation.

- Spasms may impair sleep or produce pain.

- Hip flexor and adductor spasms may impair perineal hygiene.

Little JW, Massagli TL. Spasticity and associated abnormalities of muscle tone. In: DeLisa JA, Gans BM, (eds). Rehabilitation Medicine, 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA. Lippincott-Raven, 1998.

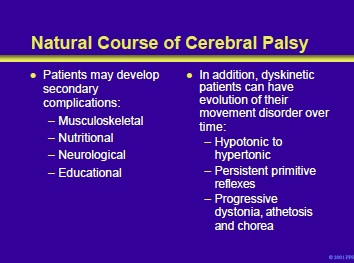

Patients with the pyramidal type of cerebral palsy and spasticity can develop a number of secondary complications including:

- Musculoskeletal (eg, contractures, scoliosis, weakness from inactivity and learned non-use)

- Nutritional problems (eg, feeding difficulties, gastroesophageal reflux)

- Neurological problems (eg, spasticity, incontinence, seating and positioning)

- Educational problems (eg, primary learning disorders or impaired cognition and impaired communication)

In addition, dyskinetic patients may show an evolution of their disorder with time:

- May evolve from hypotonic to hypertonic • May maintain primitive reflexes (to their movement disorder)

- Can show progressive dystonic, athetosis and chorea

- Go to Next section Management of spasticity in cerebral palsy Part II Passive and Active Examination

Add comment