- Details

- ICNA

- News

- Hits: 803

12th Conference of the Baltic Child Neurology Association

12th Conference of the Baltic Child Neurology Association

May 30 - June 1, 2013

Kaunas, Lithuania

The BCNA 2013 Organizers are excited to begin new year with great news. The 12th Conference of Baltic Child Neurology Association Preliminary Program has been announced!

Please find the BCNA 2013 Preliminary Program by clicking the link HERE.

Important Dates!

The BCNA 2013 Secretariat would like to remind you the important dates and deadlines worth underlining in your 2013 calendar:

1 April, 2013 - Early Registration deadline

Please register as early as possible to take the advantage of lower registration fees, to get a chance to participate at the Pre-conference Workshop and to allow efficient Conference organization. More information is available by clicking HERE.

Registration fee includes:

- Admission to all scientific sessions of the BCNA Conference

- *Admission to the Workshop "Autism: challenges and opportunities" (click HERE for special details)

- Scientific documentation and Conference bag

- Coffee breaks and lunches

- Certificate of attendance

- Welcome reception

- * Full and paid registration for the BCNA Conference before March 1, 2013, is required to attend the Workshop

Registration fee for accompanying person includes:

- Welcome reception

- Kaunas city tour

1 March, 2013 - Abstract Submission deadline

28-29 May, 2013 - Workshop "Autism: challenges and opportunities"

BCNA 2013 Organizers are happy to introduce the Workshop on autism for the participants who are directly involved in scientific and/or educational activities or deal with autism in their routine clinical practice.

Workshop on childhood autism for child neurologists "Autism: challenges and opportunities" is going to take place at the Children's Rehabilitation Hospital "Lopšelis".

We are honored to present the Invited Speakers:

- Christopher Gillberg, child psychiatrist (Sweden)

- Eva Billsted, psychologist (Sweden)

- Mark Mintz, child neurologist (USA)

- Marina Tredler, speech and language therapist (Israel)

More information regarding the Workshop and registration is available by clicking HERE.

Book a room in advance

Hotel rooms in different categories have been reserved for Conference participants. It is advisable to reserve rooms as early as possible.

Hotel booking is available via Online Registration. For more information regarding the available hotels click on the hotel name:

Hotel booking is available via Online Registration. For more information regarding the available hotels click on the hotel name:

- PARK INN Kaunas 4* (venue)

- Hotel KAUNAS 4*

- Europa Royale Kaunas 4*

- IBIS Kaunas 4*

- CENTRE Hotel Nuova 3*

- Metropolis 2*

Read More

- Details

- ICNA

- News

- Hits: 704

New research findings published in Epilepsia, indicate that having a strong family history of seizure disorders increases the chance of having migraine with aura (MA). Migraine and epilepsy often co-occur in patients. Previous studies have found that people with epilepsy are substantially more likely than the general population to have migraine headache. However, it has not been clear whether that comorbidity results from a shared genetic cause.

New research findings published in Epilepsia, indicate that having a strong family history of seizure disorders increases the chance of having migraine with aura (MA). Migraine and epilepsy often co-occur in patients. Previous studies have found that people with epilepsy are substantially more likely than the general population to have migraine headache. However, it has not been clear whether that comorbidity results from a shared genetic cause.

The study led by Dr. Melodie Winawer from Columbia University Medical Center in New York is the first to confirm a shared genetic susceptibility to epilepsy and migraine in a large population of patients with common forms of epilepsy.

For the present study, Dr. Winawer and colleagues analyzed data collected from participants in the Epilepsy Phenome/Genome Project (EPGP)—a genetic study of epilepsy patients and families from 27 clinical centers in the U.S., Canada, Argentina, Australia, and New Zealand. The study examined one aspect of EPGP: sibling and parent-child pairs with focal epilepsy or generalized epilepsy of unknown cause. Most people with epilepsy have no family members affected with epilepsy. EPGP was designed to look at those rare families with more than one individual with epilepsy, in order to increase the chance of finding genetic causes of epilepsy.

Analysis of 730 participants with epilepsy from 501 families demonstrated that the prevalence of MA—when additional symptoms, such as blind spots or flashing lights, occur prior to the headache pain— was substantially increased when there were several individuals in the family with seizure disorders. EPGP study participants with epilepsy who had three or more additional close relatives with a seizure disorder were more than twice as likely to experience MA than patients from families with fewer individuals with seizures. In other words, the stronger the genetic effect on epilepsy in the family, the higher the rates of MA. This result provides evidence that a gene or genes exist that cause both epilepsy and migraine.

Identification of genetic contributions to the comorbidity of epilepsy with other disorders, like migraine, has implications for epilepsy patients. Prior research has shown that coexisting conditions impact the quality of life, treatment success, and mortality of epilepsy patients, with some experts suggesting that these comorbidities may have a greater impact on patients than the seizures themselves. In fact, comorbid conditions are emphasized in the National Institutes of Health Epilepsy Research Benchmarks and in a recent report on epilepsy from the Institute of Medicine.

“Our study demonstrates a strong genetic basis for migraine and epilepsy, because the rate of migraine is increased only in people who have close (rather than distant) relatives with epilepsy and only when three or more family members are affected,” concludes Dr. Winawer. “Further investigation of the genetics of groups of comorbid disorders and epilepsy will help to improve the diagnosis and treatment of these comorbidities, and enhance the quality of life for those with epilepsy.”

Citation: Winawer, M. R., Connors, R. and the EPGP Investigators (2013), Evidence for a shared genetic susceptibility to migraine and epilepsy. Epilepsia. doi: 10.1111/epi.12072 [Abstract]

Related links:

Epilepsy Phenome/Genome Project (EPGP)

Read More

- Details

- ICNA

- News

- Hits: 617

The Autumn-Winter 2012 issue of the ICNA newsletter is now available to view online or to download as a PDF document.

The Autumn-Winter 2012 issue of the ICNA newsletter is now available to view online or to download as a PDF document.

This is the first issue since the 2012 12th ICNC in Brisbane, which was a phenomenal success. See the report from the team later. The AGM held at this meeting voted in favour of a trial of free membership. The effects on the membership numbers are reported in the various officer updates. This brave “experiment” appears to have succeeded in achieving the challenge to expand the membership and to promote the ICNA in its mission to be a truly global association.

This year has seen requests for an exceptional number of educational meetings under the auspices of the ICNA – most are planned for 2013 and we will hear more about them in future issues. Previously members of the board contributed to these meetings, but the planned meetings for 2013 will be represented by members from the ICNA as well as the board, who have volunteered their services.

Enjoy this issue. Please remember to send me suggestions of topics you would like included and any interesting photos. Also any brave vignettes you would like to share with fellow readers.

Click here to browse the newsletter online

OR

Click here to download the newsletter as PDF (11.5 MB)

Jo Wilmshurst

Editor

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Read More

- Details

- Dr Robert Rust

- News

- Hits: 4313

Robert Ouvrier was born on 17 May, 1940 to parents whose families had migrated to Australia in the early 19th Century. His father had been among the Australian soldiers who served with considerable distinction in combat at the Franco-Belgian front during the First World War. Not long after Robert’s birth his father was called up to serve in the Second World War as well.

Robert distinguished himself throughout his pre-collegiate education. A keen reader and student of languages, he graduated with Honors in Latin and French. His B. Sc in Medicine with Honors in Physiology was granted by the University of Sidney in 1961. M.B. and B.S degrees with Honors were granted by the University of Sydney in 1964. Dr. Ouvrier’s standing was 9th in a class of 220 and he was in addition awarded the Gillies Prize for Pathology.

Dr. Ouvrier served with distinction at successive residencies and registrarships in medicine and pediatrics that included appointments at the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital and the Royal Alexandra Hospital for Children (Sydney), the Princess Margaret Hospital (Perth), and the Royal Children’s Hospital (Melbourne), as well as six months as Registrar and then Consultant Pediatrician in New Guinea. In 1967, Dr. Ouvrier was elected a Member, the Royal Australian College of Physicians. In 1967, he was designated an Honorary Physician and Fellow in Neurology at the Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne.

In 1968 Dr. Ouvrier was honored with the Nestlé Pediatric Traveling Scholarship and in 1969 with the Postgraduate Medical Scholarship of the University of Sydney. Dr. Ouvrier chose, as did a number of particularly accomplished and pioneering Australians and at least one Englishman to pursue additional training in child neurology with David Clark at the University of Kentucky.

Unlike the Englishman, Dr. Ouvrier did not arrive with a tightly furled umbrella and bowler hat. Not unlike his contemporary Australians, Dr. Ouvrier was keen to appreciate the rural Southern culture in which he found himself and to find out what there was to learn from the cheerful purveyor of sometimes lengthy patient-centered “clinical feasts” consisting not only of clinical neurology but generous helpings of neuropathology and neuroanatomy. To this was added the humor, charm and deeply humane personality of David Clark—qualities not unlike those that have marked the career of Dr. Ouvrier.

Dr. Ouvrier’s deep classical scholarship represented another shared attainment of the mentor and mentee—Dr. Clark was known from time to time to softly pronounce from memory through his abundant moustache suitably sly-witted passages from the Roman lyric poets such as Horace. The spontaneous rich mixture of Dr. Clark’s remarks, his keen powers of observation, intellectual depth, equanimity, wisdom, and his care of and about his patients either in Lexington or in the rural outreach clinics were legendary. The rounding experience generated discussions in a manner that Dr. Clark often celebrated as an enthusiastically consumed “clinical feast” the duration of which was unpredictable though unfailingly stimulating.

Whether intrinsic or due in part to mentorship, Dr. Ouvrier’s career has been marked by these same characteristics, including personal warmth, subtle sense of humor, devotion to patients, students, fellows, colleagues, to deep learning. Whether these shared characteristics were intrinsic or due in any degree to the example of Dr. Clark, Dr. Ouvrier was understandably very much at home during nearly three years in Kentucky.

His ensuing devotion to teaching, patient care and to scientific productivity has been perhaps less voluble and more focused and selective than was at times attained in the rich interchanges of Dr. Clark’s “clinical feasts, but partakes quite similarly of the atmosphere of intellectual excitement and purpose that worked such remarkable effects on all those that trained under David Clark. A final American year was spent in Baltimore under Doctors Guy McKhann and the late John M. Freeman and in learning all that might be learned from the other distinguished members of the Johns Hopkins neurology faculty.

To these experiences has subsequently been added—as had been the case for a number of Australian child neurologists, lengthy intervals of additional rich clinical and scientific experience and mentorship in France. This “French Connection” of Australian child neurology has depended in part on the linguistic talents and appreciation of the French perspective and accomplishments of a number of Australian child neurologists that resulted in the establishment of the Association Medicale Francophone d’Australie, of which Dr. Ouvrier was elected President in 1992.

Dr. Ouvrier returned to Australia in 1972 where he was elected Fellow of the RACP and assumed a position at the Royal Alexandra and Royal Prince Alfred Hospitals. Additional appointments followed at the University of Sydney, the Royal Newcastle Hospital, the Women’s Hospital of Sydney, the Sydney Eye Hospital, and the Westmead Hospital. In 1978 he was appointed Head of the Royal Alexandra Department of Neurology and Neurosurgery, a position he was to hold for 21 years.

In 1999 he was appointed Head of the Institute of Neuromuscular Research at the Royal Alexandra Hospital for Children, serving in that position for the ensuing decade. In 2001 Dr. Ouvrier was awarded the Petre Foundation Endowed Professorship of Pediatric Neurology at the University of Sydney. A member of the Royal Australian College of Physicians since 1967, he served for eight years as a member of the Special Advisory Committee in Neurology and for seven years as a member of the Pediatrics Written Examinations Committee.

Dr. Ouvrier’s research career has been supported by seven competitive grants aimed at objectives the have included expanding understanding antiepileptic drug metabolism and utilization, four designed to study the natural history and pathophysiology of peripheral neuropathic conditions, carrying out at the same time two studies designed to develop a sophisticated screening test for impairments of higher mental function in children.

For the studies of neuromuscular conditions, Dr. Ouvrier was awarded the degree of Doctor of Medicine in the University of Sydney in 1986. The data and perspective were richly represented, along with considerable ensuing observations and discoveries of Dr. Ouvrier and his colleagues in the celebrated textbook Peripheral Neuropathy in Childhood (Ouvrier RA, McLeod JG, Pollard JD, 1990). The monograph was enlarged into a second edition in 1999. In addition to these investigations Dr. Ouvrier has directed research concerning the significance of CSF amino-acids and neurotransmitters in epilepsy. His interest in epilepsy resulted in his editing a valuable book concerning Controversies in Childhood Epilepsy in1986. Dr. Ouvrier’s distinction in these and various other fields resulted in invitations to serve as an Editorial Board Member of five journals: Brain and Development (Japan), Journal of Child Neurology (USA), Pediatric Neurology (USA, Journal of Pediatric Neurology (Turkey), and Neuromuscular Disorders (Great Britain).

Dr. Ouvrier has published 131 original full-length papers to date. They have concentrated in particular on providing enlightenment concerning peripheral neuropathic (46 papers) or myopathic/myositic (14 papers) conditions. In total to date, these papers have been cited1838 times in the original publications of other scientists and clinicians. Of the thirty papers that Dr. Ouvrier has contributed to the understanding of the genetic aspects of neurological disease, most concern nerve and muscle. Several sub-concentrations are to be found. The most extensively investigated concentration has involved two forms of the hereditary sensorimotor neuropathies first recognized by the French have received sustained attention much to the enrichment of our understanding. Three remarkable papers that consider Type III (Dejerine-Sottas disease) have together received 283 citations.

Twenty-one papers considering Type I (Charcot-Marie-Tooth) including a wonderful summary review of 80 cases published in 1987 have together been cited a total of 294 times. An additional related and particular sustained concentration of Dr. Ouvrier and his associates has resulted in twenty-one papers that have extensively investigated the progressive pes cavus deformity, to which has been added similarly detailed investigation of contractures of the hand due to progressive heritable neuropathic conditions. Dr. Ouvrier and his associates are deeply concerned, beyond questions of clinical and genetic diagnosis, first to better understand and scientifically quantify the natural history of these results of progressive peripheral neuropathic conditions.

Upon the basis of that understanding they have established novel approaches to quantification of degree of deformity and disability that have in turn afforded the opportunity scientifically to improve the design of orthoses and evaluate the effects these and other forms of therapy on slowing and ameliorating dysfunction of gait and hand use. Not least, this approach has also provided new insight into the manner in which that age-old duty and objective of the physician, the alleviation of pain. The sustained and intelligent concentration on this subject demonstrates an essential characteristic of Professor Ouvrier: the desire to leave everything he encounters professionally better for having passed through is mind and hands. He has instilled or encouraged this same sense of devotion in those whom he has trained.

Other subjects considered with similar elegance and practical importance in the original papers that Professor Ouvrier and his colleagues have published are conditions involving CNS inflammatory or infectious conditions (9 papers), movement disorders (7), endocrinopathies (4), toxicology (5), as well as developmental, embryopathic and dysmorphic conditions. Others concern screening for cognitive dysfunction (8), peripheral nerve pathology (10), heritable metabolic conditions (7), conversion disorders (2), diagnosis and treatment of epilepsy (7), opthalmological disorders (5) and so on. Among the earliest papers was an important 1970 consideration together with Ian Hopkins of stroke in children that has been cited 36 times.

Dr. Ouvrier’s 1978 description of the ocular features of Aicardi syndrome has been cited 52 times. The quite well-known first description of paroxysmal tonic upgaze by Professors Ouvrier and Billson (1988) has been cited 22 times. The stimulating paper on the quite distinctive Australian form of tick paralysis by Professors Grattan-Smith and Ouvrier has been cited 50 times. The significance of the citation figures provided here should be considered against the fact that sadly--excepting self-citation--most of the world’s medical and scientific papers achieve few if any citations.

Dr. Ouvrier’s 26 excellent book chapters organize and concentrate quite a considerable body of knowledge with precision and compelling logic that render each of them a masterly model of the approach to diagnosis and management of neurological diseases. Fourteen consider neuropathic conditions; six consider epilepsy and its treatment, while others consider infectious conditions, cerebral palsies, movement disorders, neurometabolic disorders, degenerative conditions, or Australian tick paralysis.

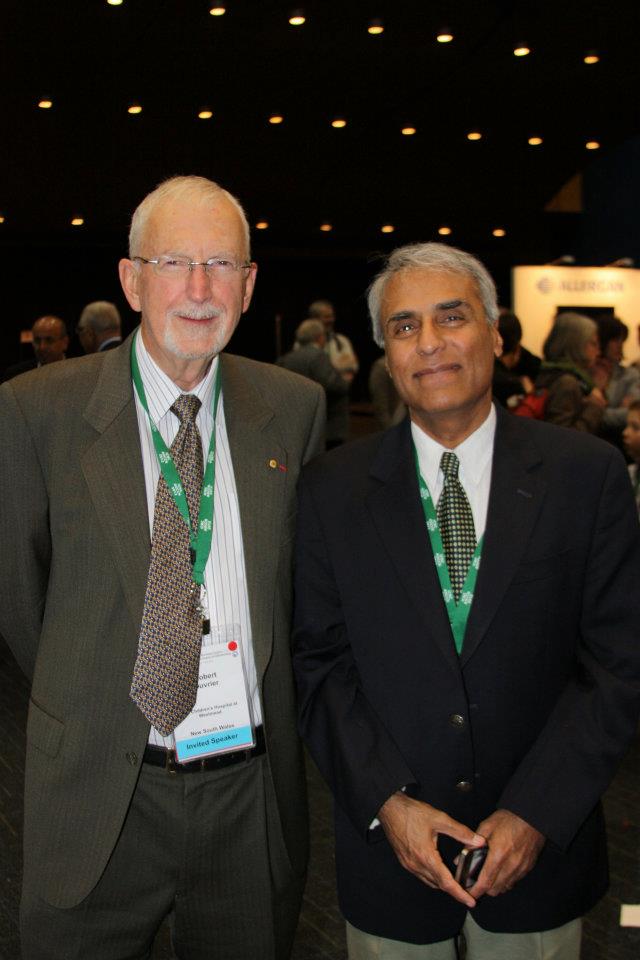

Prof. Ouvrier and Prof Chugani at the ICNC2012 Brisbane CongressTo his American and French experiences and Asian/Oceanian experiences from the outset of his career, Dr.Ouvrier has added quite remarkable professional interactions with most of the rest of the world. His lengthy service to the International Child Neurology Association has included serving as Vice President from 1975-79, assumption of a critical role during his Chairmanship of the Executive Committee and in the organization of the Second International Child Neurology Congress in Sydney in 1979. He was an ICNA Councilor from 1986-1990, Convener of the ICNA International Training Committee in 1993, and as member of the Steering Panel for the International Training and Education Committee from 1997-99. He was Editor of the ICNA Newsletter from 1994-2006. He served as ICNA President from 2006-2010.

Prof. Ouvrier and Prof Chugani at the ICNC2012 Brisbane CongressTo his American and French experiences and Asian/Oceanian experiences from the outset of his career, Dr.Ouvrier has added quite remarkable professional interactions with most of the rest of the world. His lengthy service to the International Child Neurology Association has included serving as Vice President from 1975-79, assumption of a critical role during his Chairmanship of the Executive Committee and in the organization of the Second International Child Neurology Congress in Sydney in 1979. He was an ICNA Councilor from 1986-1990, Convener of the ICNA International Training Committee in 1993, and as member of the Steering Panel for the International Training and Education Committee from 1997-99. He was Editor of the ICNA Newsletter from 1994-2006. He served as ICNA President from 2006-2010.

Dr. Ouvrier has been similarly quite active in the Asian Oceanian Child Neurology Association, serving as the Australian Delegate from 1983 to the present, as Member of the Steering Committee of the 2nd Asian Oceanian Child Neurology Congress in 1986, as Vice-President of the AOCCN from 1987-1994 Member of the AOCCN Programme Committee in 1990 and 1994, and as Chairman of the Constitution Committee from 1999 to the present. Among other international responsibilities has been Dr. Ouvrier’s service in 2010 as Member of the WHO Advisory Working Group for Revision of the ICD-10 Diseases if the Nervous System.

Few child neurologists from any country have exerted over so long an interval an impact on the International child neurology movement. He has delivered sixty-one prestigious invited lectureships throughout the world Asia, Europe, North America, South America, the Middle East, Africa, and throughout Oceania since 1977. During his Presidency of ICNA he traveled as lecturer, advisor, and organizer for the advancement of child neurology throughout the world, traveling many hundreds of thousands of miles to advance the international child neurology movement throughout the world. He has been an absolutely critical figure in the realization of the concept of which he has written movingly: enriching not only the scientific and clinical quality of ICNA, but enlarging the role the ICNA plays as an open door for the child neurology community to citizenship of the world. No one who knows Professor Ouvrier personally is at all puzzled as to why he has succeeded in achieving so much for the advancement of our international movement.

Among other reasons is the fact that almost everyone who has met him quickly attains memorable personal knowledge of his character. Open and forthright, warmly encouraging to all, a keen listener and observer, he is as the poet says, “a man who loves his fellow man”—and perhaps even more the countless children he has encountered professionally. He is a man of integrity—by which is meant the manner in which each honest element of his personality, intentions, and character fit together seamlessly into a person that has so greatly enriched the clinical and scientific substance and the worthy international objectives of our profession.

How this can be done when in fact he has for so long quietly assumed tremendous personal responsibility for the advancement of so many good ideas, so many organizations and programs, and so many individuals in need of care for their neurological problems. Yet somehow, his ever-constructive availability to all that he encounters lasts for each individual at least just long enough to form an inspirational and lasting friendship that places each individual shoulder to should with Professor Ouvrier in advancing care and understanding of many sorts throughout the world.

To these activities are added the nonprofessional interests that Professor Ouvrier has cultivated throughout his life. He is an avid sportsman—tennis, skin-diving, surfing, and others, he has remained throughout his life as did David Clark a Latin scholar up to the challenge of even the most difficult Roman lyric poets. He is exceptionally knowledgeable of Western classical music—with particular keenness for Sibelius, and he has understanding in depth of history of science, medicine, and the history of the world. Such richness of attainment is a private matter to him—he hasn’t the slightest degree of ponderous exhibitionism in sharing all of the things that he knows. But these facts, as with the facts that constitute his knowledge of medicine and science, are ready quietly to be added as needed with modesty to enrich one or another particular conversation or answer a particular important question.

In addition to Professor Ouvrier’s other achievements, honors, and awards, several honors were quite extraordinary. In 2001 he was named Chevalier de l’Ordre National du Mérite, Republic of France and has subsequently designated Chevalier de l’Ordre de la Legion d’Honneur, Republic of France. In 2004 he was decorated with the Order of Australia. Yet there is on even greater attainment and it is a shared one that has enriched the whole of his professional life. It dates back to the acceptance of his proposal of marriage to Margo, a nurse who became his wife.

Together this pair has garnered the respect and love of an international collection of friends and colleagues. Together they raised a family of three children who have grown into accomplished adults—Sarah, Priscilla, and Richard. To date there are as well there are three grandchildren

- Details

- ICNA

- News

- Hits: 720

Preliminary results from the FEBSTAT study has revealed that within days of a prolonged fever-related seizure, some children have signs of acute brain injury, abnormal brain anatomy, altered brain activity, or a combination.Febrile Seizures affect 3 to 4 percent of all children. Most such children recover rapidly and do not suffer long-term health consequences. However, having one or more prolonged febrile seizures in childhood is known to increase the risk of subsequent epilepsy which is estimated to be about 30-40 percent following febrile status epilepticus (FSE).

Preliminary results from the FEBSTAT study has revealed that within days of a prolonged fever-related seizure, some children have signs of acute brain injury, abnormal brain anatomy, altered brain activity, or a combination.Febrile Seizures affect 3 to 4 percent of all children. Most such children recover rapidly and do not suffer long-term health consequences. However, having one or more prolonged febrile seizures in childhood is known to increase the risk of subsequent epilepsy which is estimated to be about 30-40 percent following febrile status epilepticus (FSE).

The Consequences of Prolonged Febrile Seizures in Childhood (FEBSTAT) study is focused specifically on FSE and the risk of temporal lobe epilepsy.Within days of FSE, the children in the study underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and electroencephalography (EEG). The MRI findings were reported in July 2012, and the EEG findings were reported in November 2012. Both papers were published in Neurology.

FEBSTAT began almost 10 years ago. 199 Children, aged between one month and six years with FSE were enrolled from 2003-2010 at five sites: Montefiore Medical Center and Jacobi Hospital in the New York City; Lurie Children's Hospital in Chicago; Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C.; Virginia Commonwealth University Hospital in Richmond; and Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk.A further 96 children who had experienced a single, simple febrile seizure (lasting 10 minutes or less) were also recruited and served as the comparison (control) group.

The children underwent blood tests, a neurological exam, MRI, and EEG within 72 hours of being seen in the emergency room for FSE. The blood samples are being analyzed for viral infections linked to febrile seizures and for the presence of gene mutations that could contribute to epilepsy. The children continue to receive neurological exams, MRI and EEG at regular intervals.

The MRI scans revealed that FSE is sometimes associated with abnormalities in the hippocampus. Of 191 children with FSE, 22 (11.5 percent) had signs of hippocampal injury on MRI, and 20 (10.5 percent) had developmental abnormalities of the hippocampus. Abnormal MRI results were rare among children with simple febrile seizures, defined as lasting 10 minutes or less. Out of 96 children with such seizures, only two (2.1 percent) had developmental abnormalities of the hippocampus and none had signs of brain injury.

Nearly half (45.2 percent) of the children with FSE had abnormal EEG findings. There was also a correlation between the MRI and EEG findings. Children with evidence of acute brain injury after FSE were more than twice as likely to have abnormal EEG findings. The results suggested that in some children prolonged febrile seizures do result in brain injury. In some others pre-existing brain abnormalities may increase the susceptibility to febrile seizures. Both these situations could eventually lead to epilepsy. But it will take more time for the study to confirm this, especially as it usually takes between 8 and 11 years for TLE to develop following FSE.

Temporal lobe epilepsy can cause memory loss, and neuroimaging of adults with temporal lobe epilepsy have sometimes revealed shrinkage and cell loss within the temporal lobe and hippocampus. Many adults with the disorder also report a history of FSE.

If MRI and EEG findings associated with FSE ultimately do correlate with epilepsy, they could be used to identify kids who are at risk and who might benefit from research on preventative therapies for epilepsy.

FEBSTAT is supported by grant NS043209 to Dr. Shinnar. Data from children with simple febrile seizures were taken from a study led by Dale C. Hesdorffer, Ph.D., of Columbia University in New York. That study ended in 2004, and was supported by grant HD036867 from NIH's Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

References:

- M. J. Berg, B. Abou-Khalil. Childhood febrile status epilepticus: Chicken or egg? Does it matter? Neurology, 2012; 79 (9): 840 DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182684559

- S. Shinnar, J. A. Bello, S. Chan, D. C. Hesdorffer, D. V. Lewis, J. MacFall, J. M. Pellock, D. R. Nordli, L. M. Frank, S. L. Moshe, W. Gomes, R. C. Shinnar, S. Sun. MRI abnormalities following febrile status epilepticus in children: The FEBSTAT study. Neurology, 2012; 79 (9): 871 DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318266fcc5

Read More