- Details

- ICNA

- News

- Hits: 945

Researchers have shown that they were able to improve muscle function in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy mice using in vivo gene editing techniques.

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) affects about 1 out of 5000 male births and caused by mutations in the dystrophin gene. Though DMD has been a target for gene therapy for a long time, progress has been very slow and attempts unsuccessful.The dystrophin gene has 79 sections, or exons, but can retain reasonable function even if a few exons in the middle are lost. Dystrophin works as long as its two ends are intact as in the case of Becker muscular dystrophy, in which frame shift mutations result in abnormal translation of the dystrophin gene.

New gene-editing techniques are now promising to make a substantial progress towards a treatment for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy.Genome editing has the potential to restore expression of a modified dystrophin gene from the native locus to modulate disease progression by inserting the correct gene into the damaged cells. Removing one or more exons from the mutated transcript can produce an in-frame mRNA and a truncated, but still functional, protein.

An alternative treatment, using antisense oligonucleotides which are now in clinical trials works on the same principle of avoiding damaged exons, but instead of cutting them out of the DNA, they bind to the mutated exon, so that when the gene is then translated from the mature mRNA, it is “skipped” over, restoring the disrupted reading frame, which would still result in a largely functional protein.

Using the CrisprCas9 gene editing technique, researchers can cut the DNA of chromosomes at selected sites to remove or insert segments.

Three independent research groups have reported in the journal Science on 31 December 2015 that using the CrisprCas9 technique they were able to successfully treat mice with a defective dystrophin gene. All three groups had used a viral vector loaded with the DNA editing components to infect the muscle cells in DMD mouse and excise from the gene a defective exon. Without the defective exon, the muscle cells made a shortened truncated dystrophin protein which remained functional, giving the mice more strength.

The three teams were led by Charles A. Gersbach of Duke University, Eric N.Olson of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and Amy J.Wagers of Harvard University.

Eric N. OlsonIn 2014, the Olson group had reported on the successful editing out of the damaged 21st exon in a fertilized agg of the DMD mouse, thus causing an inheritable change to its genome. In this study they used adeno-associated virus-9 (AAV9) to deliver gene editing components to postnatal mdx mice. The gene editing components were directed to cut the two ends of the 21st exon. They tested different modes of AAV9 delivery including intra-peritoneal at postnatal day (P1), intra-muscular at P12, and retro-orbital at P18 and found that all three methods restored dystrophin protein expression in cardiac and skeletal muscle to varying degrees and expression increased from 3 to 12 weeks post-injection.

Eric N. OlsonIn 2014, the Olson group had reported on the successful editing out of the damaged 21st exon in a fertilized agg of the DMD mouse, thus causing an inheritable change to its genome. In this study they used adeno-associated virus-9 (AAV9) to deliver gene editing components to postnatal mdx mice. The gene editing components were directed to cut the two ends of the 21st exon. They tested different modes of AAV9 delivery including intra-peritoneal at postnatal day (P1), intra-muscular at P12, and retro-orbital at P18 and found that all three methods restored dystrophin protein expression in cardiac and skeletal muscle to varying degrees and expression increased from 3 to 12 weeks post-injection.

Postnatal gene editing also enhanced skeletal muscle function, measured by grip strength tests 4 weeks post-injection.The virus had successfully infected muscle cells throughout the mouse’s body, snipping out the exon from the dystrophin gene.The muscle cells repaired the DNA by joining the pieces of the cut chromosome and generated an effective dystrophin protein.

Charles A. GersbachGersbach's group had also reported earlier in 2015 that using the CrisprCas9 technique they were able to remove the 45th to 55th exons of the dystrophin gene from Duchenne

Charles A. GersbachGersbach's group had also reported earlier in 2015 that using the CrisprCas9 technique they were able to remove the 45th to 55th exons of the dystrophin gene from Duchenne

patient cell cultures. In their current study they also used the adeno-associated virus to deliver the CRISPR/Cas9 system to the mdx mouse model of DMD to remove the mutated exon 23 from the dystrophin gene. They used local and systemic delivery to adult mice and systemic delivery to neonatal mice.

Exon 23 deletion by CRISPR/Cas9 resulted in expression of the modified dystrophin gene, partial recovery of functional dystrophin protein in skeletal myofibers and cardiac muscle, improvement of muscle biochemistry, and significant enhancement of muscle force.

Amy WagersWager's group on the other hand looked specifically at whether the genealtering virus could infect stem cells. In their study, they also used adeno-associated virus (AAV) of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-Cas9 endonucleases coupled with paired guide RNAs flanking the mutated Dmd exon23 which resulted in excision of intervening DNA and restored Dystrophin reading frame in myofibers, cardiomyocytes, and muscle stem cells following local or systemic delivery. AAV-Dmd CRISPR-treatment partially recovered muscle functional deficiencies and generated a pool of endogenously corrected myogenic precursors in mdx mouse muscle.

Amy WagersWager's group on the other hand looked specifically at whether the genealtering virus could infect stem cells. In their study, they also used adeno-associated virus (AAV) of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-Cas9 endonucleases coupled with paired guide RNAs flanking the mutated Dmd exon23 which resulted in excision of intervening DNA and restored Dystrophin reading frame in myofibers, cardiomyocytes, and muscle stem cells following local or systemic delivery. AAV-Dmd CRISPR-treatment partially recovered muscle functional deficiencies and generated a pool of endogenously corrected myogenic precursors in mdx mouse muscle.

It is unclear whether CRISPR technique could be used to correct other types of mutations or how the viral vectors or the modified dystrophin gene may react with the human immune system.

Although gene therapy has been tried for Duchenne Muscular Dystophy in the past, there seems to be a real chance now of it being successful. All the three research groups have filed for patents and are optimistic that clinical trials could be launched in the near future.

Citations:

Long C, Amoasii L, Mireault AA, McAnally JR, Li H, Sanchez-Ortiz E et al. (2015) Postnatal genome editing partially restores dystrophin expression in a mouse model of muscular dystrophy.Science ():. DOI: 10.1126/science.aad5725 PMID: 26721683.

Tabebordbar M, Zhu K, Cheng JK, Chew WL, Widrick JJ, Yan WX et al. (2015) In vivo gene editing in dystrophic mouse muscle and muscle stem cells.Science ():. DOI: 10.1126/science.aad5177 PMID:26721686.

Nelson CE, Hakim CH, Ousterout DG, Thakore PI, Moreb EA, Rivera RM et al. (2015) In vivo genome editing improves muscle function in a mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy.Science ():. DOI: 10.1126/science.aad5143 PMID: 26721684.

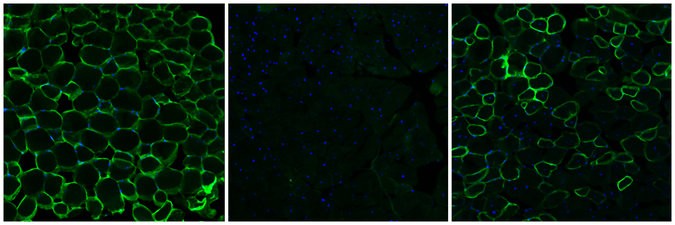

Cover image: Cross sections of muscle tissue from mice showing from left to right: normal healthy tissue, tissue with DMD and tissue after gene editing treatment source: Christopher Nelson, Duke University

Read More

- Details

- ICNA

- News

- Hits: 787

In a paper published on Jan. 4, 2016, in the online Early Edition of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers from Penn State University reports on the discovery of a novel drug target, which could help in the treatment for Rett Syndrome and other forms of autism-spectrum disorders.

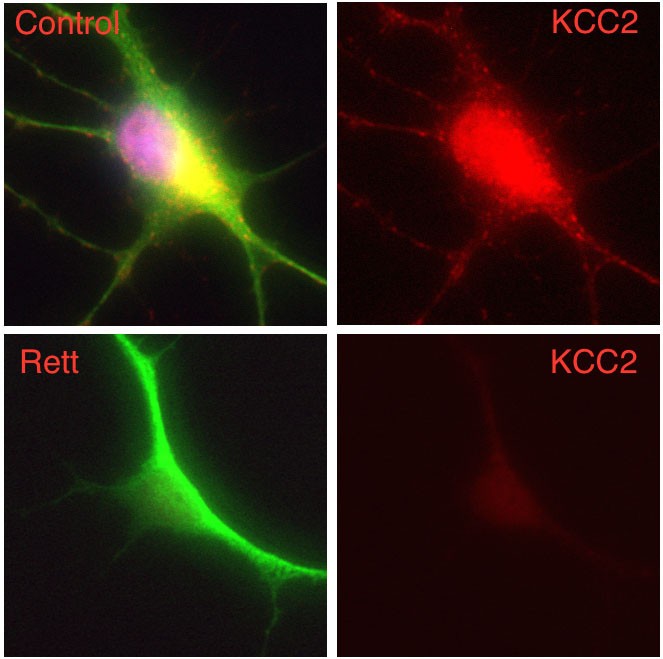

In this work, the researchers demonstrate that human neurons derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) from patients with Rett syndrome (Rett neurons), show a significant deficit in neuron-specific K+-Cl− cotransporter2 (KCC2) expression, leading to an impaired GABA functional switch from excitation to inhibition. Restoring KCC2 level rescued GABA functional deficits in Rett neurons.

They also showed that treating diseased nerve cells with insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) elevated the level of KCC2 and corrected the function of the GABA neurotransmitter. IGF1 has been shown to alleviate symptoms in a mouse model of Rett Syndrome and is the subject of an ongoing phase-2 clinical trial for the treatment of the Rett syndrome in humans.

Rett syndrome is a severe form of autism spectrum disorder, mainly caused by mutations of a single gene methyl CpG binding protein 2 (MeCP2) on the X chromosome. Patients with Rett syndrome exhibit a period of normal development followed by regression of brain function and the emergence of autistic behaviour.

Tang and colleagues in this study further demonstrate that MeCP2 regulates KCC2 expression through inhibiting RE1-silencing transcriptional factor REST, a neuronal gene repressor, suggesting a potential therapeutic approach for the treatment of Rett syndrome through modulation of KCC2.

These findings open up the possibility of identifying more small molecules that can act on KCC2 to treat Rett syndrome and other autism spectrum disorders.

The research was led by Gong Chen, professor of biology and the Verne M. Willaman Chair in Life Sciences at Penn State. In addition, the research team also includes Xin Tang , Julie Kim, Li Zhou, Lei Zhang, and Zheng Wu at Penn State; Eric Wengert at Bucknell University; Carol Marchetto and Fred Gage at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies; and Cassiano Carromeu and Alysson Muotri at the University of California - San Diego.

The research was funded by grants from National Institutes of Health (MH083911 and AG045656) and a Stem Cell Fund from the Penn State Eberly College of Science.

Citation: Xin Tang, Julie Kim, Li Zhou, Eric Wengert, Lei Zhang, Zheng Wu, Cassiano Carromeu, Alysson R. Muotri, Maria C. N. Marchetto, Fred H. Gage, and Gong Chen. KCC2 rescues functional deficits in human neurons derived from patients with Rett syndrome. PNAS 2016 ; published ahead of print January 5, 2016, doi:10.1073/pnas.1524013113

Cover image: Composite image of a human nerve cell derived from a patient with Rett syndrome showing significantly decreased levels of KCC2 compared to a control cell. Image courtesy: Gong Chen lab, Penn State University

Read More

- Details

- Harry Chugani

- News

- Hits: 1693

Charles Kennedy, one of the first child neurologists in the USA, passed away on October 6, 2015 in Maine at the age of 95 following a brief illness. Born in Buffalo, NY, he attended Nichols School and later Deerfield Academy. He graduated from Princeton University with honors in Chemistry in 1942.

At Princeton, in addition to preparing for medical school, he was also a member of the choir, glee club and the Princeton Nassoons (an all male a cappella group). He went on to receive his MD degree at the University of Rochester while in the Navy V-12 program. Internship was at Yale New Haven Hospital during which time World War II ended. After the war, he remained on active duty in the Navy where he was assigned to the Veterans Administration Psychiatric Hospital in Canandaigua, NY.

Following his 2 years of military service, he went through a pediatrics residency at the Childen’s Hospital of Buffalo. Neurology and Child Neurology training was with Sidney Carter at the Neurological Institute in New York. During this time, Kennedy and Carter published an article on optic neuritis in children and the risk for multiple sclerosis, a paper that spurned future research . Following his fellowship, Charles was appointed Chief of Neurology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Kennedy had a very strong interest in the cerebral blood flow and metabolic requirements of the developing brain. Very early in his career, he developed a close collaboration with Louis Sokoloff, also a physician scientist who never practiced medicine except during internship at Philadelphia General Hospital. As early as 1957, Kennedy et al. (J Clin Invest) used the Kety-Schmidt method (a modification of the Fick Principle) to show for the first time that children require higher cerebral blood flow and oxygen utilization than adults.

In 1967, Kennedy took a sabbatical at the Laboratory of Cerebral Metabolism at the NIH, working with Louis Sokoloff. That sabbatical was a life changing event for Kennedy who decided not to return to his position in Philadelphia but to pursue his research collaboration with Sokoloff at the NIH. He split his time between NIH and Georgetown University School of Medicine, where he was Professor and Chief of Child Neurology. The following years were highly productive and scientifically rewarding. Sokoloff and Kennedy became life-long friends and colleagues; they complemented each other with their skills. A series of experiments investigated the use of various carbon-14 labeled radiotracers and quantitative autoradiography to measure cerebral blood flow.

In 1977, Sokoloff, Reivich , Kennedy and the group published the seminal paper in Journal of Neurochemistry on the 14C-2-deoxyglucose method for the measurement of local cerebral glucose utilization in the rat brain. This method has been widely used in various experimental paradigms in a number of species. Importantly, the method provides the basis for the measurement of glucose metabolism in humans using positron emission tomography (PET), which is now routinely used in the clinical setting.

Lou Sokoloff (left) and Charles Kennedy (right) at the NIH

Lou Sokoloff (left) and Charles Kennedy (right) at the NIH

At Georgetown, Kennedy trained a number of child neurologists who went on to pursue academic careers, including Bennett Lavenstein, Harry Chugani, and Pauline Filippek. He demonstrated great skill clinically. Indeed, there are few who excel both in the clinic and in the laboratory. One of us (HC), as a medical student at Georgetown, was so impressed by his clinical/research activities that I took an elective with Dr. Kennedy at NIH after which I decided to pursue a career in child neurology with a similar area of research. For all those who came in contact with Charles Kennedy he embodied the characteristics of a physician scholar, gentleman, advisor, confidante and role model.

Charles maintained his humor even into his 90’s. He once said: “if you are my age, and you don’t have heart disease or cancer, I guess you just wait for organ failure!” Kennedy is survived by his wife, Eulsum Kennedy, a talented sculptor and painter (of North Korean descent). He joked about her as well by saying: “the reason I remain slim is that my wife has put me on a North Korean diet!” Kennedy is also survived by his sister Florence Davidsen of Iowa City, and 3 children from a previous marriage: Allen Kennedy of NYC, Jacqueline MacMillan of Sommerville, Mass, and Carol Radmer of Valley Park, Mo, and 2 grandchildren. We will miss you Charles.

Harry T. Chugani, MD (Wilmington, DE)

Bennett Lavenstein, MD (Washington, DC)

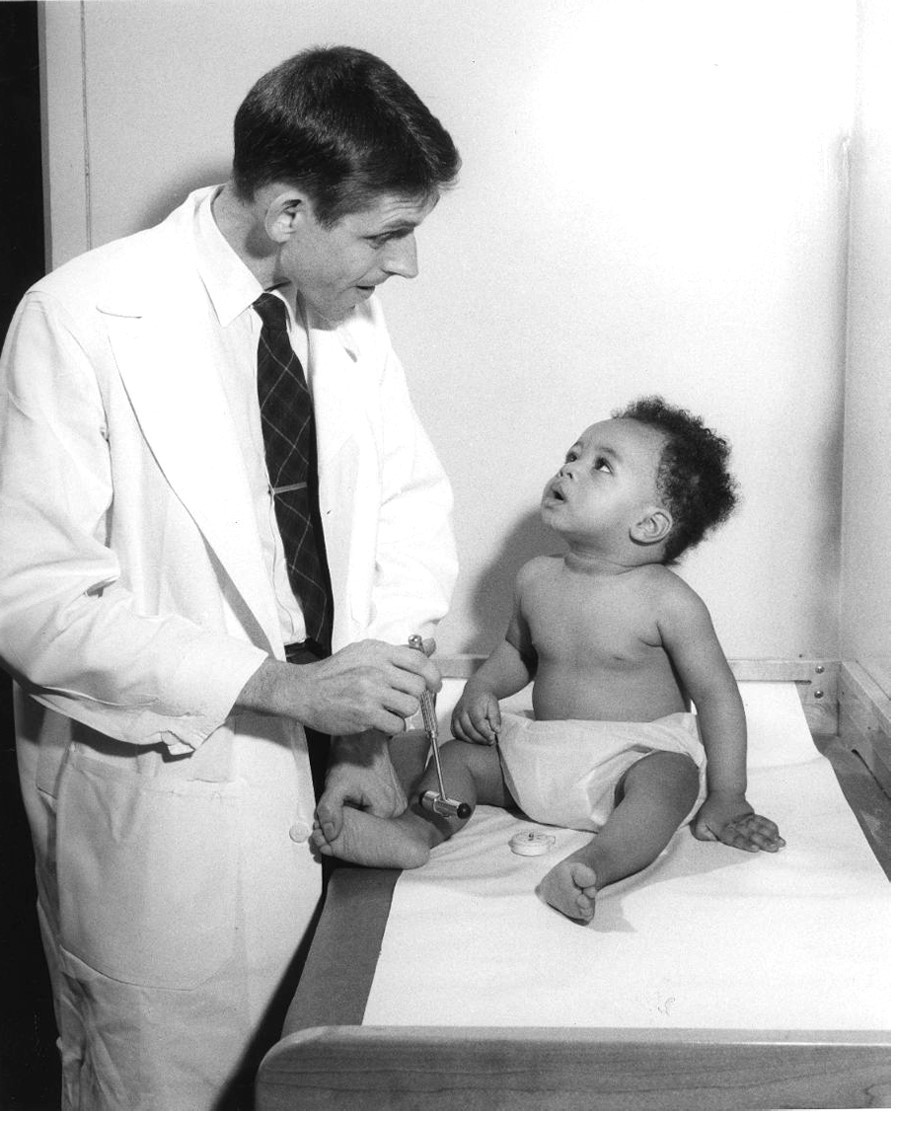

Cover photo: Charles Kennedy, MD at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

Citations: Sokoloff L, Reivich M, Kennedy C, Des Rosiers MH, Patlak CS, Pettigrew KD et al. (1977) The [14C]deoxyglucose method for the measurement of local cerebral glucose utilization: theory, procedure, and normal values in the conscious and anesthetized albino rat.J Neurochem 28 (5):897-916. PMID: 864466.

Read More

- Details

- Coriene Catsman-Berrevoets

- News

- Hits: 751

The 2nd meeting of the Posterior Fossa Society will take place at the Convention Centre Liverpool on Sunday, June 12th 2016.

The Posterior Fossa Society is an international group of researchers and health care professionals (doctors, nurses, psychologists, speech pathologists, linguists, neuroscientists etc.) who are dedicated to research into the causes, features, treatment and prevention of the postoperative Cerebellar Mutism Syndrome (CMS) and Cerebellar Cognitive Affective Syndrome (CCAS) in children and adults. It reaches its goals by systematically gathering and exchanging information on the CMS and CCAS, both online and during international meetings and conferences.

In the first meeting in Reykjavik, Iceland in June 2015, the definition of postoperative Cerebellar Mutism Syndrome was addressed. In the meeting of the Posterior Fossa Society in Liverpool, the focus will be on prevention and treatment of symptoms. The meeting is open to members and non-members of the Society.

In addition to lectures of experts in the field, in the program, one session is reserved for free papers and opportunity for poster presentations.

Abstract submission for free paper session and posters: You are invited to submit abstracts on the topics of prevention of postoperative CMS and treatment of CMS symptoms. All abstracts are to be submitted on line and should be a maximum of 300 words. The abstract should mention:

'Abstract for PFS meeting'

Title of your abstract,

Author and Co-authors

Abstract text (maximum 300 words)

Presentation preference (platform or poster presentation)

Registration fee:

Early registration (1st of January to 25th of March- 2016) £75.00

Standard registration: (25th of March-13th of May 2016) £95.00

Late registration: (13th of May- 15th of June 2016) £125.00

Registration fees include conference material, lunch and refreshments. Participants of the PFS meeting are invited to the SIOP & PFS Dinner on the 11th June evening at 7.30pm – Maritime Museum Albert Dock - £35 per person.

Please note that the program of the Posterior Fossa Society meeting is specifically designed to compliment the 90 minute session on Cerebellar Mutism Syndrome in the main ISPNO meeting for which abstract submission is also welcome.

see http://www.ispno2016.com/pfs.php for more details

Read More

- Details

- ICNA

- News

- Hits: 819

Twelfth Göttingen Meeting of the German Neuroscience Society (March 22 – 25, 2017)

The Göttingen Meeting of the German Neuroscience Societies is one of the largest multi-disciplinary neuroscience meetings in Europe with around 1.700 participants. It covers a wide range of research fields in the neurosciences including vertebrate and invertebrate systems, molecular, cellular and systemic neurobiology, neuropharmacology, developmental, computational, behavioral, cognitive and clinical neuroscience.

The call for symposia for the 12th Göttingen Meeting of the German Neuroscience Society is open now. Symposia dealing with all areas of neuroscience research are invited. The application must be submitted via the meetings website. The meeting's language is English.

The deadline for submissions is Monday, February 15, 2016.

36 symposia (i.e. six symposia in six parallel sessions) with will be accepted.

- The symposium proposal must contain the following information:

- The title of the symposium

- The name of the organizer(s)

- A short description of the symposium

- The name and address of each of the four intended speakers

- The titles (tentative) of the talks

The organisers must adhere to the following rules:

- Organizers of a symposium in 2015 are not entitled to organize a symposium in 2017

- The title for the symposium should be succinctly worded and should not exceed 100 characters including spaces.

- The proposal should contain a short description in English not exceeding 5.000 characters including spaces.

- Members of the program committee can be invited speakers of a symposium but cannot be the sole organizer of a symposium.

- The duration of a symposium is 2 hours. The maximum number of speakers if four. The affiliation and the (tentative) title of each speaker must be provided.

- Two oral communications by young predoctoral students must be included in the symposium. These will be selected by the symposium organizer from the abstracts submitted in fall 2016.

Symposia are self-supporting, it is the obligation of the symposium organizer to raise the necessary funds for the symposium. The German Neuroscience Society cannot guarantee financial support. Both the organizers and the invited speakers of a symposium have to pay registration fee.

Read More

- Etiology remains unknown in recent Acute Flaccid Paralysis cases in North America

- Recurrent strep A infections and autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorder in children:possible new link

- Manipulating consciousness using deep brain stimulation

- Combination of hormone therapy With Vigabatrin reduces Infantile Spasms better than hormone therapy alone