- Details

- ICNA

- News

- Hits: 5087

Tiina Talvik was born in April 21 in 1938 into a family of teachers. She graduated from The University of Tartu in 1962 and started her career as pediatrician and pediatric neurologist at Tartu Children`s Hospital. From the very first moments of her medical career she was enthusiastic, not only for her research but also for taking care of her patients. After working for a few years, she started to appreciate the importance of genetics and started a medico-genetical service in Estonia. This made her a pioneer of the field at the time. She started working as a geneticist in 1968 and was Head of the Laboratory of Medical Genetics of the Tartu Clinical Hospital, one of founders of the medico-genetical service in Estonia. She worked in the field of medical genetics until 1974, when she was invited to the Dept of Neurology and Neurosurgery of the Tartu University. She was an associate professor in the department since 1990 and created pediatric neurology as an independent specialty. This period of her life involved research, teaching and developing the specialty in Estonia. For 30 years she guided her students in the research of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, oxidative stress and asphyxia.

Tiina Talvik was born in April 21 in 1938 into a family of teachers. She graduated from The University of Tartu in 1962 and started her career as pediatrician and pediatric neurologist at Tartu Children`s Hospital. From the very first moments of her medical career she was enthusiastic, not only for her research but also for taking care of her patients. After working for a few years, she started to appreciate the importance of genetics and started a medico-genetical service in Estonia. This made her a pioneer of the field at the time. She started working as a geneticist in 1968 and was Head of the Laboratory of Medical Genetics of the Tartu Clinical Hospital, one of founders of the medico-genetical service in Estonia. She worked in the field of medical genetics until 1974, when she was invited to the Dept of Neurology and Neurosurgery of the Tartu University. She was an associate professor in the department since 1990 and created pediatric neurology as an independent specialty. This period of her life involved research, teaching and developing the specialty in Estonia. For 30 years she guided her students in the research of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, oxidative stress and asphyxia.

Professor Tiina Talvik’s influence reached across borders. She played a role in bringing together all pediatric neurologists in the Baltic States with the creation of the Baltic Child Neurology Association. The association still holds congresses every two years.

From 2000 to 2003 she was the head of The Children’s Clinic of Tartu University Hospital and the head of the department of Pediatrics of Tartu University. She really motivated her younger colleagues to be interested in research and so 17 doctoral theses were done under her supervision. She was also the coauthor for over 200 scientific articles. During these years Children`s Clinic became very innovative and dedicated to publishing scientific research.

From 2003 professor Tiina Talvik inspired young researchers as professor emeritus.

Due to her active research and social activities she has been acknowledged several times: a Research Award in Medicine from The Republic of Estonia, a medal from Tartu University and Tartu City, the Order of the Estonian Red Cross class I medal, award of The Republic of Estonia for long term research work, Life Work as a Geneticist Award, Award of The University of Tartu. Professor Tiina Talvik was nominated an honorary citizen of Tartu and a cavalier of the Honorary Citizen of the City of Tartu and holder of the Grand Star of Tartu decoration.

Professor Talvik was also the Honorary President of the Estonian Society of Pediatric Neurology, being the teacher of all pediatric neurologists in Estonia. She was also an honorary member of The Estonian Pediatric Society and The Estonian Association of Neurologists and Neurosurgeons.

In addition to pediatric neurology and genetics, she was also highly passionate about the rights of patients and their loved ones. She stayed very active in the committee of Medical Ethics of Tartu University Hospital.

Professor Tiina Talvik was very strong-willed in standing for the rights of disabled people. She was the leading lecturer in the first teaching courses in rehabilitation and started science-based rehabilitation in Estonia.

During the past years she was actively involved in The Estonian Agrenska Foundation and was the head of the organisation since 2003 with the aim to improve the life of families with disabled children.

She was a remarkable doctor, a talented teacher, a loyal friend, a loving wife, mother and grandmother. Her infectious laughter will be missed.

Source: EPNS

- Details

- ICNA

- News

- Hits: 16423

This narrative review from JAMA Neurology summarize available information regarding coronaviruses in the nervous system, identify the potential tissue targets and routes of entry of SARS-CoV-2 into the central nervous system, and describe the range of clinical neurological complications that have been reported thus far in COVID-19 and their potential pathogenesis.

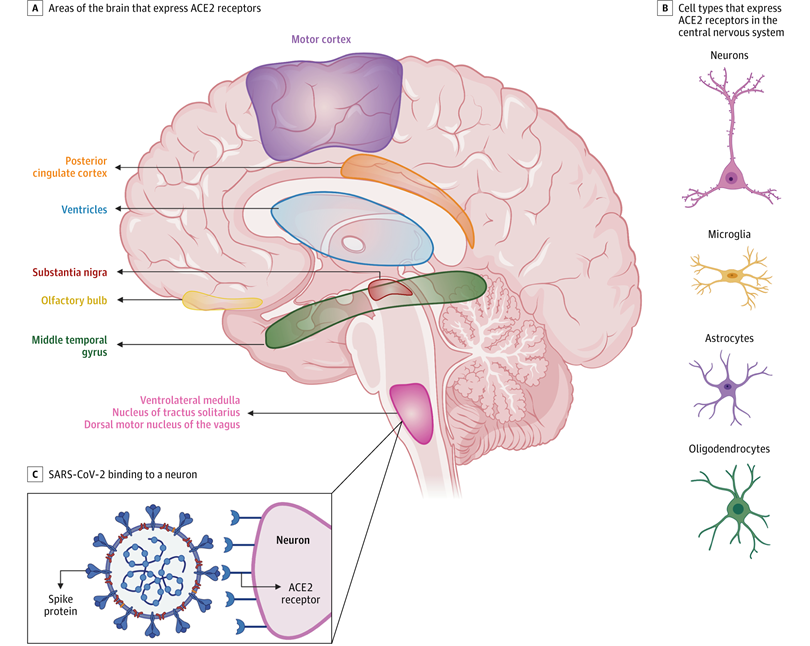

Emerging data suggest that ACE2 receptors are expressed in multiple regions of the human and mouse brain, including the motor cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, ventricles, substantia nigra, olfactory bulb, middle temporal gyrus, ventrolateral medulla, nucleus of tractus solitarius, and dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve (A) and on several key cell types that make up the central nervous system, including neurons, microglia, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes (B).35-37 C, ACE2 receptors on a medullary neuron binding to the SPIKE protein on severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). [Ref: Zubair AS, et al. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(8):1018–1027]

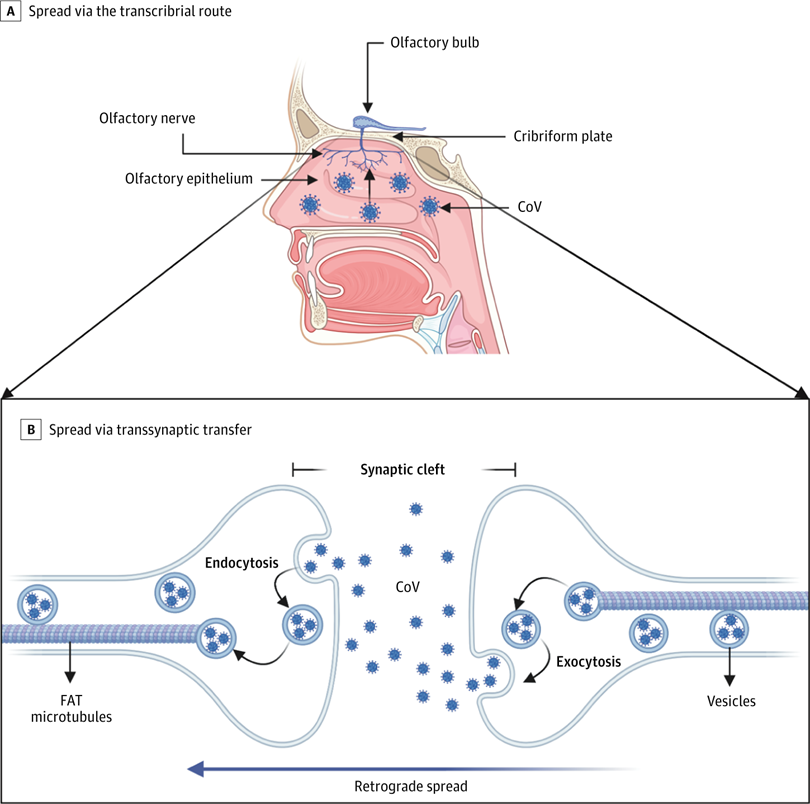

A, Coronavirus (CoV) has been shown to spread via the transcribrial route from the olfactory epithelium along the olfactory nerve to the olfactory bulb within the central nervous system. B, CoV has been shown to spread retrograde via transsynaptic transfer using an endocytosis or exocytosis mechanism and a fast axonal transport (FAT) mechanism of vesicle transport to move virus along microtubules back to neuronal cell bodies.

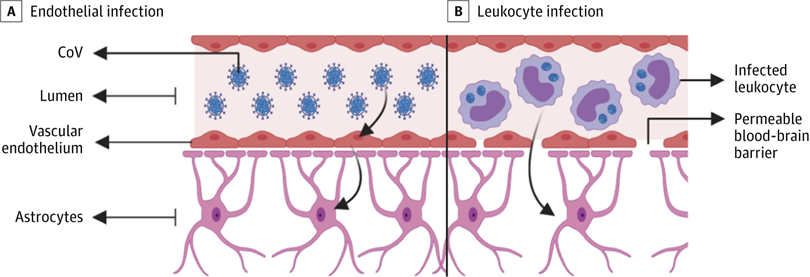

A, Infected vascular endothelial cells have been shown to spread severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) to glial cells in the central nervous system. B, Known as the Trojan horse mechanism, infected leukocytes can cross the blood-brain barrier to infect the central nervous system. CoV indicates coronavirus

Reference:

Zubair AS, McAlpine LS, Gardin T, Farhadian S, Kuruvilla DE, Spudich S. Neuropathogenesis and Neurologic Manifestations of the Coronaviruses in the Age of Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Review. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(8):1018–1027. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.2065

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaneurology/fullarticle/2766766

- Details

- ICNA

- News

- Hits: 6150

According to research presented at the 2021 Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA) Virtual Clinical and Scientific Conference, on the SPR1NT trial Children with SMA treated with onasemnogene abeparvovec-xioi (Zolgensma®; Novartis) prior to the onset of symptoms, achieved milestones like sitting, standing and walking at an appropriate age, grew as expected without nutritional assistance, and remained free of all forms of mechanical ventilatory support. These findings further underscore the urgent need for newborn screening.

According to research presented at the 2021 Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA) Virtual Clinical and Scientific Conference, on the SPR1NT trial Children with SMA treated with onasemnogene abeparvovec-xioi (Zolgensma®; Novartis) prior to the onset of symptoms, achieved milestones like sitting, standing and walking at an appropriate age, grew as expected without nutritional assistance, and remained free of all forms of mechanical ventilatory support. These findings further underscore the urgent need for newborn screening.

As a gene therapy, ZOLGENSMA® (onasemnogene abeparvovec-xioi) is designed to target the genetic root cause of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) by replacing the function of the missing or nonworking SMN1 gene with a new, working copy of a human SMN gene. ZOLGENSMA does not change or become a part of the child’s DNA. You can watch a short video of how it works here.

The phase 3 SPR1NT trial (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03505099) is an ongoing open-label, single-arm study evaluating the efficacy and safety of onasemnogene abeparvovec in presymptomatic patients (6 weeks of age and younger) with a genetic diagnosis of SMA and 2 or 3 copies of survival motor neuron 2 gene (SMN2). As of June 11, 2020, 79% of patients (n=11/14) with a median age of 15.6 months in the 2-copy cohort, met the primary endpoint of sitting without support for at least 30 seconds; 10 patients achieved this mark within the World Health Organization (WHO) window of normal development. Moreover, 36% of patients (n=5/14) were able to stand independently and 29% (n=4/14) could walk independently. Among patients who had not achieved these milestones, the researchers reported that the majority had not yet passed the normal development window.

Additionally, all patients achieved Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Infant Test of Neuromuscular Disorders (CHOP INTEND) scores of at least 50, with 93% of patients (n=13/14) achieving a CHOP INTEND score of at least 58. Steady gains in mean raw score of Bayley-III fine and gross motor scales were observed in all patients.

Among the 3-copy cohort, 53% of patients (n=8/15) with a median age of 15.2 months met the primary endpoint of standing alone for at least 3 seconds, while 40% (n=6/15) were able to walk independently. Patients who had not yet achieved these milestones were reported to still be within the WHO window of normal development. Steady gains in mean raw score of Bayley-III fine and gross motor scales were observed in all of these patients.

Zolgensma is currently approved for the treatment of pediatric patients less than 2 years of age with SMA with bi-allelic mutations in the SMN1 gene. The recombinant adeno-associated virus vector-based gene therapy is designed to deliver a copy of the gene encoding the human SMN protein.

Reference

New Zolgensma data demonstrate age-appropriate development when used early, real-world benefit in older children and durability 5+ years post-treatment. [press release]. Basel, Switzerland: Novartis; March 15, 2021.

- Details

- ICNA

- News

- Hits: 2648

- Details

- ICNA

- News

- Hits: 5653