- Webinars

- 4. Rehabilitation Management

4. Rehabilitation Management

Hot

This section will discuss rehabilitation management in the patient with cerebral palsy and spasticity.

{akeebasubs !*}

The content you are accessing is restricted to members only. Please login or sign up for a membership to gain unrestricted access.

Useful links

Apply for an ICNA (International Child Neurology Association) Membership

Apply for an ACNA (African Child Neurology Association) Membership

The membership to both the above orgarnisations are currently FREE

The role of rehabilitation in the patient with cerebral palsy is to increase the child’s motor control of the upper and lower extremity and improve function in daily occupations of productivity (academic work), play and self-care (eating, dressing, personal hygiene). The process is ongoing and conducted in an integrated fashion.

{akeebasubs *}

The process of rehabilitation in patients with cerebral palsy consists of evaluating the child’s functional abilities and sensorimotor/biomechanical differences associated with spasticity and the selection of appropriate treatments to increase function based on evidence-based outcomes.

Consequently, the role of the therapist in this process is the following:

- Serve as a referral source in the community

- Participate as a member of a multidisciplinary team

- Assist in movement analysis

- Prepare the child and family for intervention(s)

- Strengthen muscles and improve motor control

- Assist with setting realistic goals

- Adapt splints and orthoses

- Plan for future interventions

- Evaluate the outcomes of treatment

- Assist in developing oral motor skills

The focus of therapy (occupational and physical) is to increase the patient’s ability to perform daily tasks.

Rehabilitation treatment options for patients with cerebral palsy include the following:

- Casting

- Orthotics/splints

- Strengthening

- Electrical stimulation

- Practice of functional tasks

- Sensory integration

- Muscle stretching

- Targeted muscle training

The success of many of the rehabilitation options can be facilitated by the appropriate use of the various interventions discussed in this slide kit including BTX.

Therapeutic exercises that can be employed in the rehabilitation management of the child with spasticity include:

- Stretching and range of motion

- Active assistive, active and resistive exercise

- Exercises that will harness co-contraction in a beneficial fashion

- Endurance training

Neurodevelopmental training (NDT) is based on rehabilitative principles that focus on managing neuromotor problems in the child with spasticity by:

- Normalizing postural tone

- Inhibiting/integrating abnormal reflexes

- Facilitating normal movements

While the efficacy of this approach is not well documented in the literature, therapists often integrate some elements of NDT with other interventions.

Functional training is an important component of rehabilitation management.

It includes:

- Self-care activities

- Bed mobility

- Sitting training (eg, coming to sit, sitting balance, sitting mobility [scooting])

- Transfer training (eg, bed, toilet, tub, wheelchair, car, van, school bus, classroom)

- Wheelchair mobility (eg, self propelled vs power driven, consider powered mobility for even very young children, transportation of chair) and seating systems (eg, enhance mobility, maximize UE and respiratory function, minimize deformity, maintain skin integrity, allow child the opportunity to interact with the environment, development of cognitive and communication skills)

- Gait training (eg, household and/or community, bracing, walker, crutches, cane, advanced ambulation skills such as curbs, ramps and stairs)

- Skills for recreation activities and sports (eg, one leg standing, pivoting, running, stooping)

- School therapy (eg, work with multidisciplinary team to enhance education)

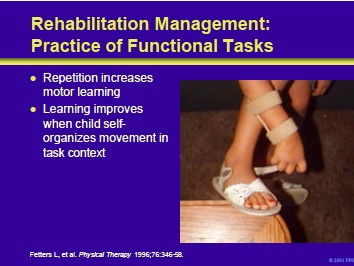

Repetition increases motor learning. Learning improves when child self-organizes movement(s) in the context of various tasks.

Tasks can also be practiced in the context of adaptive equipment. For example, the results of practice in reaching were documented in children with spastic quadriplegia. Patients demonstrated greater changes in movement time post-practice intervention than with neurodevelopmental therapy intervention.

Children in both treatment groups demonstrated reduced movement time and movement units in reaching with both therapy interventions; however, reaction time did not change with either intervention.

Fetters L, Kluzik J. The effects of neurodevelopmental treatment versus practice on the reaching of children with spastic cerebral palsy. Physical Therapy 1996;76:346-58.

Serial casting provides prolonged stretch. The procedure progressively increases muscle length and passive range of motion. It consists of 5-7 days of casting with recasting at a new muscle length for 3 weeks. It is particularly useful when the patient’s disorder has a significant static component. BTX injections can be employed to correct the dynamic component of the defect prior to casting.

The use of orthoses is an integral component of the process of rehabilitation. They can be made for an individual joint or region. Most are fabricated from thermoplastic, metal, or light casting material.

The appliances may be either custom made or adapted from commercial orthotic devices. Indications include correct alignment, maintain muscle length, control forces at the joint and control the degree of freedom during performance of various tasks.

Static orthoses support the target joint(s). They require adjustment or replacement to maintain increased range of motion and to prevent deformities as the child grows. Static orthoses support the joint, prevent contractures, prevent some movements and retain movement gained through various rehabilitation mobilization techniques.

Dynamic orthoses are made with hinges or joints to provide movement. Posterior leaf spring orthoses may also be used. Dynamic orthoses align joints, resist movement, assist movement and stimulate movement.

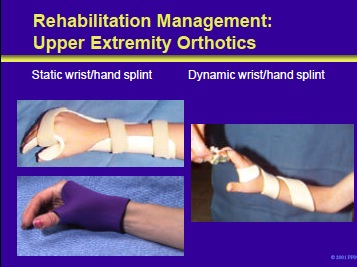

Full wrist static splints (left panel) are required when flexor spasticity predominates the hand posture with no active extension recorded. Shortened spastic muscles are elongated to reduce dynamic contractures at joints. Lever arm principles are used by applying forces at the end of lever arms and counter forces through straps.

Specific positioning of the hand supports the distal transverse arch of the hand to preserve mobility at the metacarpal heads while thumb position preserves the C-shaped web spaces. Serial casting may be employed to gain the tissue length and mechanical alignment prior to static splinting. Dynamic splints impose movement and force to assist the child in completing tasks.

These splints are used with the child who demonstrates weak but active control of extensors and flexors. The spiral splint in the right panel provides active wrist extension for the child in reaching.

The splint allows the child to actively flex the wrist causing the splint to unspiral. As the child relaxes, the splint returns to the initial position of wrist extension

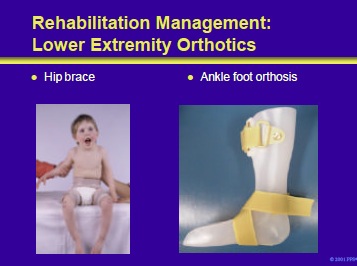

Orthoses are an appropriate component of the management of children with cerebral palsy and diplegia or hemiplegia. This slide illustrates examples of a hip brace and an ankle foot orthosis (AFO).

Dynamic or static hip orthoses can be used to address hip adduction contractures. Prior to the orthosis, the adductors and/or medial hamstrings are injected with BTX.

Ankle foot orthoses can support dynamic stretching and strengthening during gait. A floor reaction AFO (Saltiel) may provide the appropriate biomechanical correction in children with crouched gait or apparent equinus. It may also be useful after hamstring injections to support the quadriceps while strengthening.

Strengthening programs can be used to strengthen weak antagonist muscles and the corresponding spastic agonists. In adolescents with cerebral palsy, 6 weeks of isokinetic exercise was shown to increase upper extremity movement time and torque.

The effects were greater for these patients than for a matched group of children who received repetitive practice with no resistive exercise and a control group with no intervention.

McCubbin JA, Shasby GB. Effects of isokinetic exercise on adolescents with cerebral palsy. Adapt Phys Act Q 1985;2:56-64.

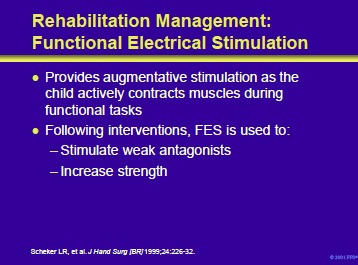

Functional electrical stimulation (FES) provides augmentative stimulation as the child actively contracts muscles during functional tasks. Following BTX therapy, the initial intervention occurs approximately 2 weeks after the injection and is used to stimulate weak antagonists and strengthen weak spastic muscles.

The efficacy of FES in conjunction with dynamic splinting was demonstrated by Scheker et al in 19 children with spastic cerebral palsy. Combined modality therapy in this group produced a significant improvement in upper extremity function and decreased spasticity.

Scheker LR, Chesher SP, Ramirez S. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation and dynamic bracing as a treatment for upperextremity spasticity in children with cerebral palsy. J Hand Surg [Br] 1999;24:226-32.

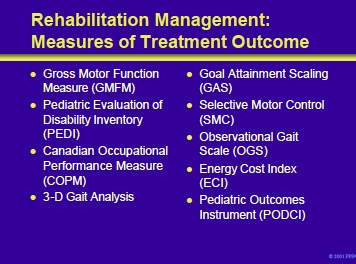

Outcome measures listed on the slide include many of those discussed before. In addition, the following measures can also be used to provide a baseline and to measure treatment outcome: •

- Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM): is an individualized criterion referenced measure where patient/family set goals based on problems in three general areas of self care, productivity and leisure. Developed and validated on children and adults with a variety of diagnoses.

- Goal Attainment Scaling (GAS): individualized criterion referenced measure where specific goals are developed, prioritized and weighted with the interviewer. Criteria for change are also negotiated.

- Selective Motor Control (SMC): developed to measure isolated muscle control of the dorsiflexors after BTX. Muscle control graded 0 to 3+ in this simple test.

- Observational Gait Scale (OGS): components of the gait cycle are ranked. Designed to measure change over time. A clinical alternative to instrumented gait analysis.

- Energy Cost Index (ECI): simple clinical replacement for oxygen consumption test. Calculates energy cost from heart rate, walking speed and distance walked.

Law M, King G, MacKinnon E, et al. All about outcomes: An educational program to help you understand, evaluate, and choose pediatric outcome measures [computer program]. Thorofare, NJ: Slack Incorporated; 1999.

- Next Section: Oral Medications for the Treatment of Spasticity

{/akeebasubs}