Self-Limited Epilepsy with Centrotemporal Spikes (SeLECTS)

(formerly called childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes, benign epilepsy of childhood with centrotemporal spikes or Benign Rolandic Epilepsy)

- Self-Limited Epilepsy with Centrotemporal Spikes (SeLECTS), is the most common focal epilepsy syndrome of childhood, accounting for 15–20% of all childhood epilepsies.

- age-dependent epilepsy, with a typical onset at 5–8 years

- incidence is approximately 6.1 per 100,000 children aged <16 years per year[1]

- Both sexes are affected, with a slight male predominance (60%)

- Most of the time it is a self-limiting epileptic syndrome, with seizure remission within adolescence

- Seizures are overall relatively infrequent, with 60–70% of patients experiencing two to ten seizures lifetime and 10–20% only one

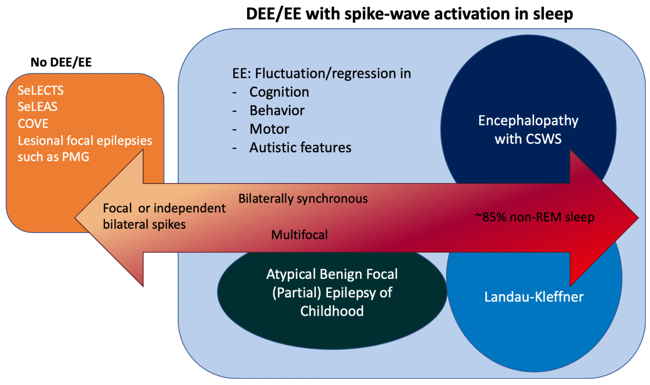

- Rarely Children with SeLECTS evolve to Developmental and/or Epileptic Encephalopathy with spike-wave activation in sleep (D/EE-SWAS)which is distinguished by cognitive and language regression

- D/EE-SWAS incorporates the several syndromes previously named Landau-Kleffner syndrome, Epileptic encephalopathy with continuous spike-waves during sleep and Atypical benign partial epilepsy (pseudo-Lennox syndrome). All these conditions share some EEG features.

Seizure Semiology

- Seizures are brief, typically less than 2-3 minutes

- usually few in number (most children have less than 10 lifetime seizures) and may occur sporadically, with frequent seizures seen over a few days or weeks and then several months until

the next seizure

- Seizures occur during sleep in 80-90% of patients and only while awake in fewer than 20% of children

- Seizures are usually stereotyped, self-limiting focal (hemifacial) motor with associated sensory features

- somatosensory symptoms, with unilateral numbness or paresthesia of the tongue, lips, gums, and inner cheek

- orofacial motor signs, specifically tonic or clonic contraction of one side of the face, mouth and tongue, then involving one side of the face

- speech arrest – children have difficulty or are unable to speak (dysarthria or anarthria) but can understand language

- sialorrhea, a characteristic ictal symptom (unclear whether it is due to increased salivation, swallowing disturbance, or both.)

- seizures may evolve to a focal to bilateral tonic-clonic seizure1)

- cognitive (e.g. gustatory hallucinations), emotional(e.g. fear), and autonomic features are not seen2)

EEG

- normal background activity

- High amplitude centrotemporal sharp-and-slow wave complexes that activate in drowsiness and sleep are mandatory for diagnosis.

- Triphasic, high-voltage (100-microvolts to 300microvolts) sharp waves (initial low-amplitude positivity, then high amplitude negativity followed again by low amplitude positivity), with a transverse dipole (frontal positivity, temporo-parietal negativity), often followed by a high voltage slow wave.

- The discharges may be isolated or occur in trains of doublets and triplets, and focal, rhythmic, slow activity is occasionally observed in the same region as the spikes.

- The discharges may be unilateral or bilateral and independent

- There may be discharges seen outside the centrotemporal region (midline, parietal,frontal, occipital).

- A marked increase in the frequency of epileptiform activity in drowsiness and sleep always occurs.

- The EEG pattern may also change such that sharp- or spike-and-slow waves have a broader field and become bilaterally synchronous

- In 10-20% of children, centrotemporal sharp- or spike-and-slow wave may be activated by sensory stimulation of the fingers or toes

- Seizures may be accompanied by a brief decrease in amplitude of the background EEG, followed by diffuse sharp wave discharges of increasing amplitude, predominantly in one centrotemporal region, followed by high amplitude slowing and then a return to the usual interictal EEG.

- With focal to bilateral tonic-clonic seizures, ictal rhythms may become bilaterally synchronous (as opposed to generalized) sharp- or spike-and slow-wave activity

Genetics

- Centrotemporal spikes can be a trait that is passed down through siblings in a way that depends on their age and is autosomally dominant, even if they don't have seizures.

Practice Points

- If a continuous spike-and-slow-wave pattern is present in sleep, the child should be evaluated for progressive language or cognitive impairment or regression. This EEG pattern should only lead to a diagnosis of D/EE-SWAS if developmental plateauing or regression is also present[4].

- Patients with SeLECTS may show “atypical” symptoms, such as starting their seizures early (<4 years old), having side effects from AEDs, having different types of seizures, having seizures that can't be controlled or a history of status epilepticus, having seizures during the day, having atypical EEG abnormalities or peculiar EEG abnormalities activation during sleep, and having developmental delay or neurologic deficits before the seizures start. It is important carry out cognitive and neuropsychological assessments at the time of diagnosis and during the follow-up to trace the trajectories of neuropsychological development of these patients more deeply.

Treatment

- As the seizures associated with SeLECTS often stop around the age of puberty, it is not clear whether it is necessary to prescribe ASMs to all children who present with this condition.

- When considering the use of antiseizure medications for SeLECTS, it is important to have a thorough discussion with the individual, their family, and caregivers (if applicable). This discussion should focus on developing a personalized medication strategy based on the specific epilepsy syndrome, treatment objectives, and the preferences of the individual and their family or caregivers.

- lamotrigine and levetiracetam should be considered as first-line treatment[5]

- As second-line treatment, carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine and zonisamide are recommended

- school performance is a good indicator of cognition since it measures processing and retention.If any deterioration is noted, an EEG should be performed to exclude Developmental and/or epileptic encephalopathy with spike-wave activation in sleep D/EE-SWAS. A neuropsychology assessment to review academic performance should also be performed.

References

1

If a child has atypical absence seizures, focal atonic seizures, or focal motor seizures with negative myoclonus, loses their balance, and falls, this could mean they have progressed to D/EE-SWAS. It is important to look for evidence of cognitive difficulties or regression.

2

if prolonged focal non-motor seizures with prominent autonomic features, especially ictal vomiting is present then Self-Limited Epilepsy with Autonomic Seizures (SeLEAS) (formerly called Panayiotopoulos syndrome or early-onset benign occipital epilepsy) should be considered

1.

a

. International League Against Epilepsy classification and definition of epilepsy syndromes with onset in childhood: Position paper by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions. Epilepsia. 2022 Jun;63(6):1398-1442. doi: 10.1111/epi.17241. Epub 2022 May 3.

[PMID: 35503717] [DOI: 10.1111/epi.17241]

[PMID: 35503717] [DOI: 10.1111/epi.17241]

2.

a

. Mutations in GRIN2A cause idiopathic focal epilepsy with rolandic spikes. Nat Genet. 2013 Sep;45(9):1067-72. doi: 10.1038/ng.2728. Epub 2013 Aug 11.

[PMID: 23933819] [DOI: 10.1038/ng.2728]

[PMID: 23933819] [DOI: 10.1038/ng.2728]

3.

a

. Update on the genetics of the epilepsy-aphasia spectrum and role of GRIN2A mutations. Epileptic Disord. 2019 Jun 1;21(S1):41-47. doi: 10.1684/epd.2019.1056.

[PMID: 31149903] [DOI: 10.1684/epd.2019.1056]

[PMID: 31149903] [DOI: 10.1684/epd.2019.1056]

4.

a

. Idiopathic focal epilepsies: the "lost tribe". Epileptic Disord. 2016 Sep 1;18(3):252-88. doi: 10.1684/epd.2016.0839.

[PMID: 27435520] [DOI: 10.1684/epd.2016.0839]

[PMID: 27435520] [DOI: 10.1684/epd.2016.0839]

5.

a

National Guideline Alliance (UK). Effectiveness of antiseizure medications for self-limited epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes: Epilepsies in children, young people and adults: Evidence review Q. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2022 Apr. (NICE Guideline, No. 217.) Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK581163/

Discussion